Karlag

1950

The Karaganda region occupies a special place in the history of the GULAG. Since the early 1930s, an extensive system of corrective labor camps was established there, each with its own specificity.

The Karaganda Corrective Labor Camp (KarLag, 1931–1959) was one of the largest, both in area (comparable to the territory of France) and in the number of inmates. It was through KarLag that the highest number of representatives of the intelligentsia passed under Article 58 (under it, the so-called "enemies of the people" were convicted): well-known scientists and cultural figures.

1953

On March 5, Stalin died.

"Ülo Sooster and his work endured plenty... Seven out of the ten promised years, he dedicated to the most common form of communication between man and power – the Gulag. To the frustration and surprise of the rulers, he survived, breathed, sketched, and loved."

Boris Zhutovsky, artist

1950

In the summer of 1950, Ülo Sooster was sent to a labor camp. He was assigned to the fire brigade, where he became friends with the young poet Roman Sef, who had been exiled to the camp at the age of 15 as the son of enemies of the people.

Yuri Sobolev, an artist, friend, and colleague of Ülo, recalled: "Sooster always remembered the concentration camp... He befriended many remarkable people there and worked a lot. He said that this very concentrated, compressed, and comprehensible life cultivated in him such a level of freedom. I encountered such a manifestation of freedom for the first time and was amazed."

1951–1953

From the labor camp's work records, it is evident that Ülo worked as a firefighter, stoker, plumber, and painter.

Whenever he had the chance, he continued to draw, and for this, he was repeatedly punished with solitary confinement.

After learning Russian in the camp, Sooster gained the opportunity to work as an artist in the cultural and educational department.

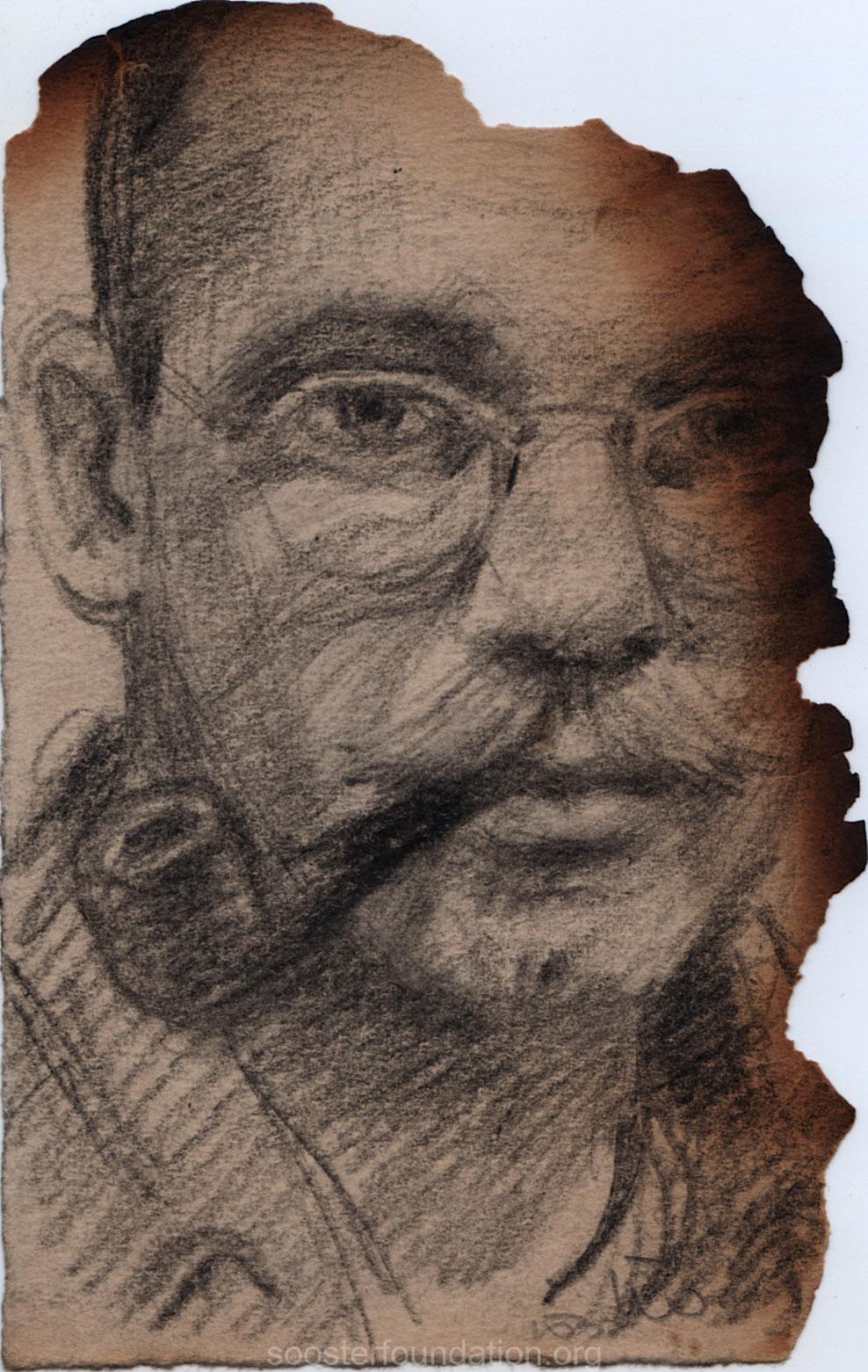

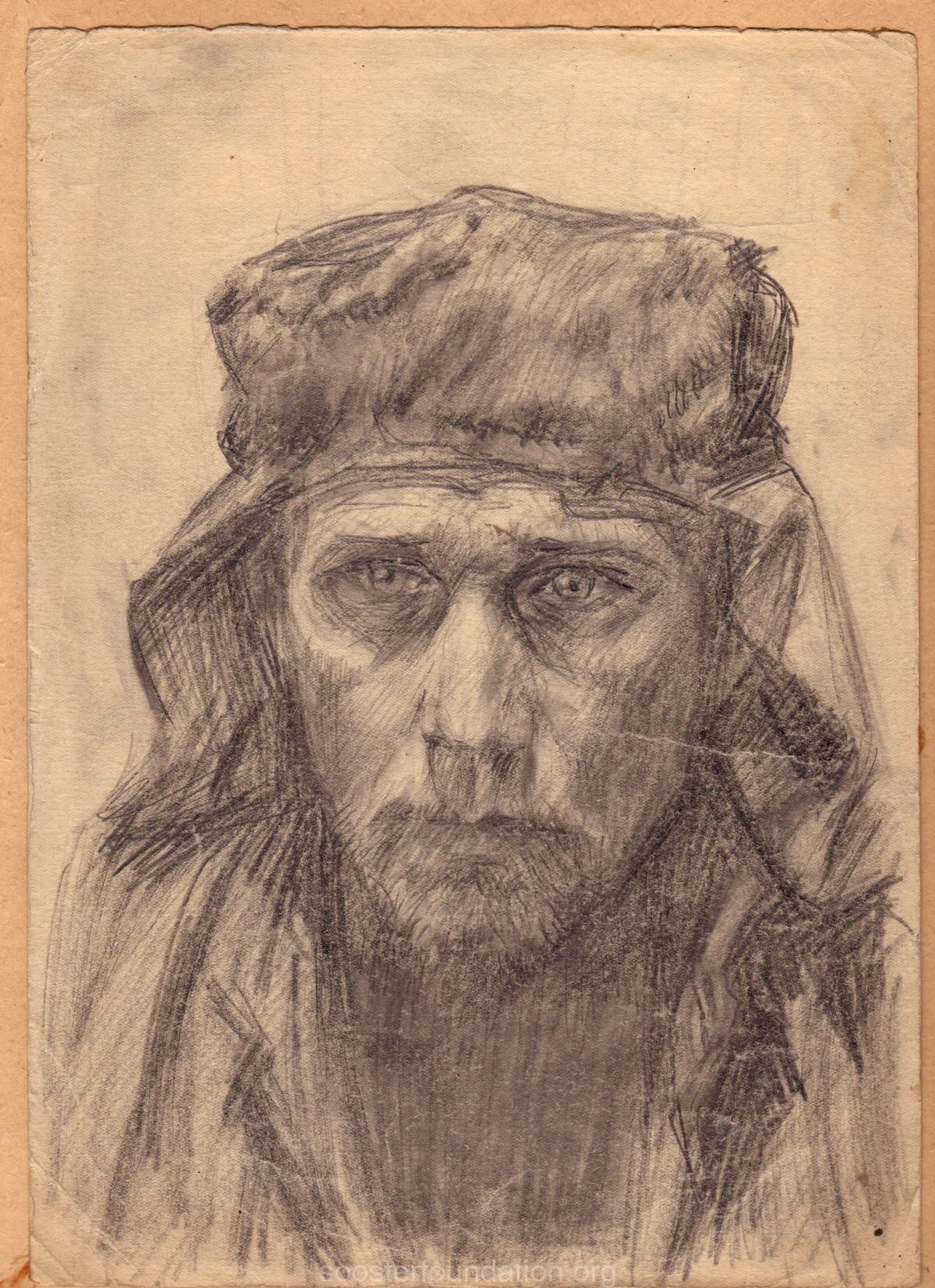

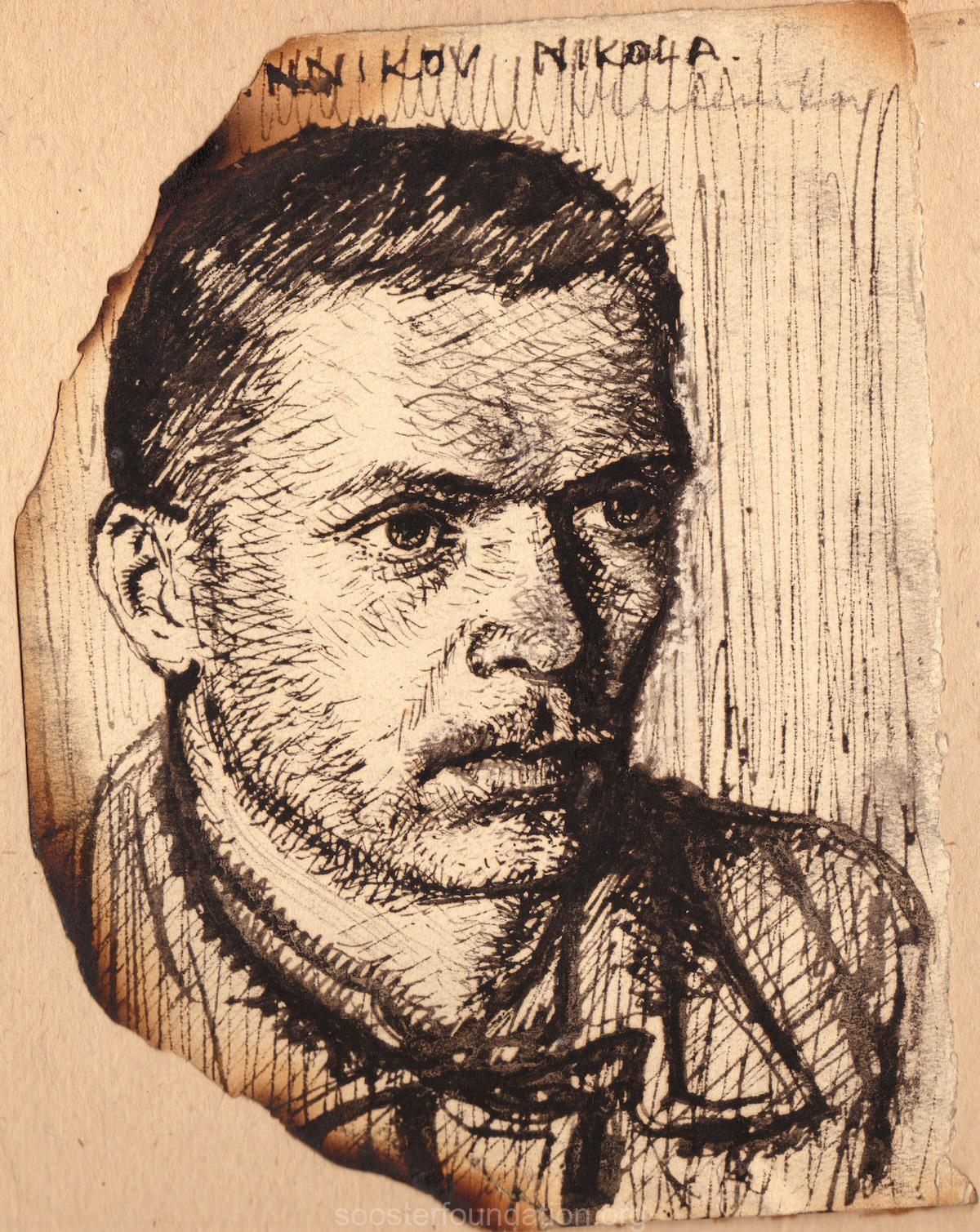

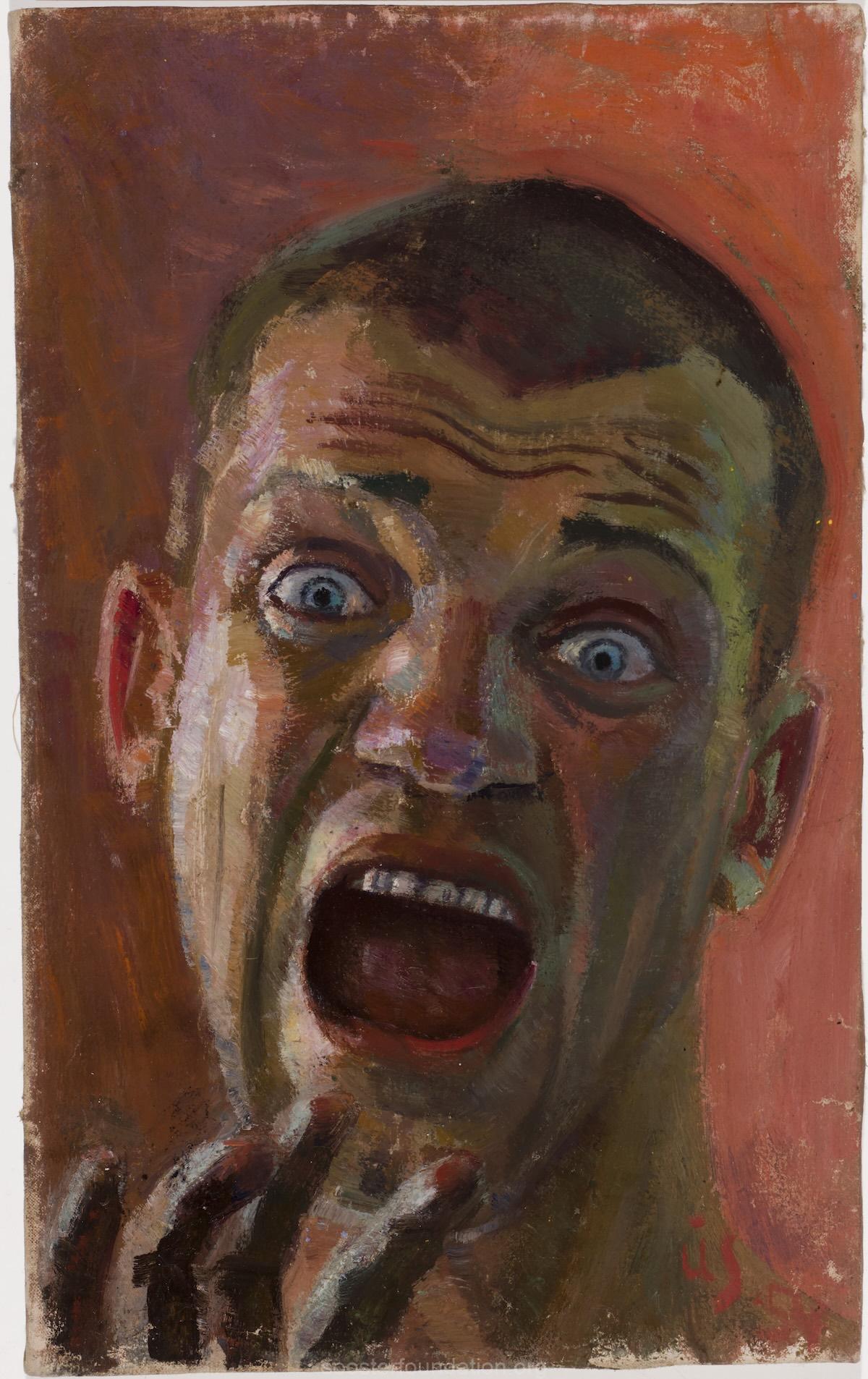

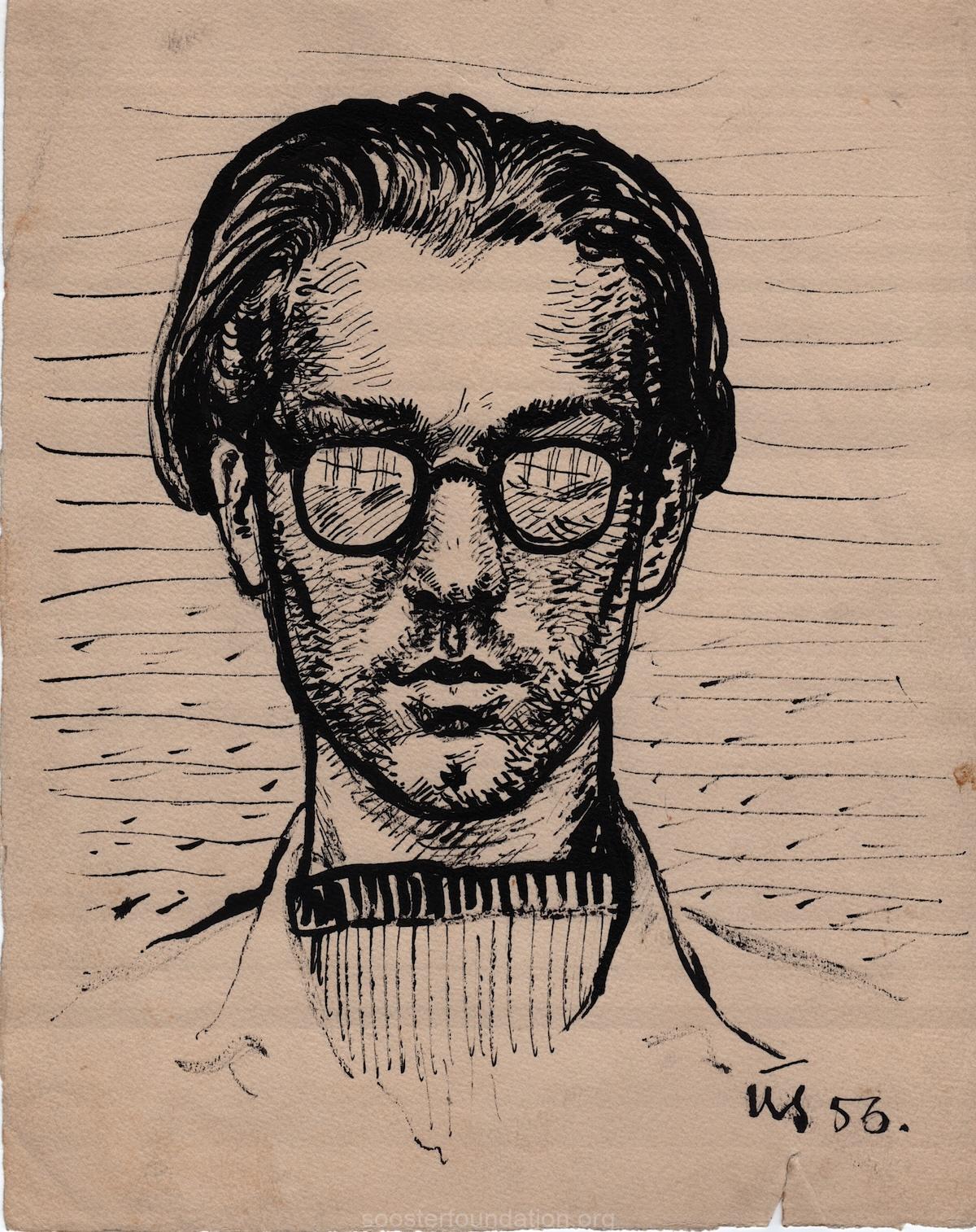

However, while working as a camp artist had strict boundaries, personal drawing was strictly prohibited in high-security camps. On one occasion, a guard discovered Sooster’s drawings of the camp and portraits of prisoners and threw them into the fire. Ülo managed to snatch a stack from the flames, for which the guard knocked out his front teeth. This is why, in one of his self-portraits from the camp period, we see Ülo with metal teeth. The burnt drawings were hidden and later secretly smuggled out of the camp. As a result, they survived in the family archive, with their edges singed by fire.

1953

Ülo Sooster got a position as an artist in the inter-camp House of Culture.

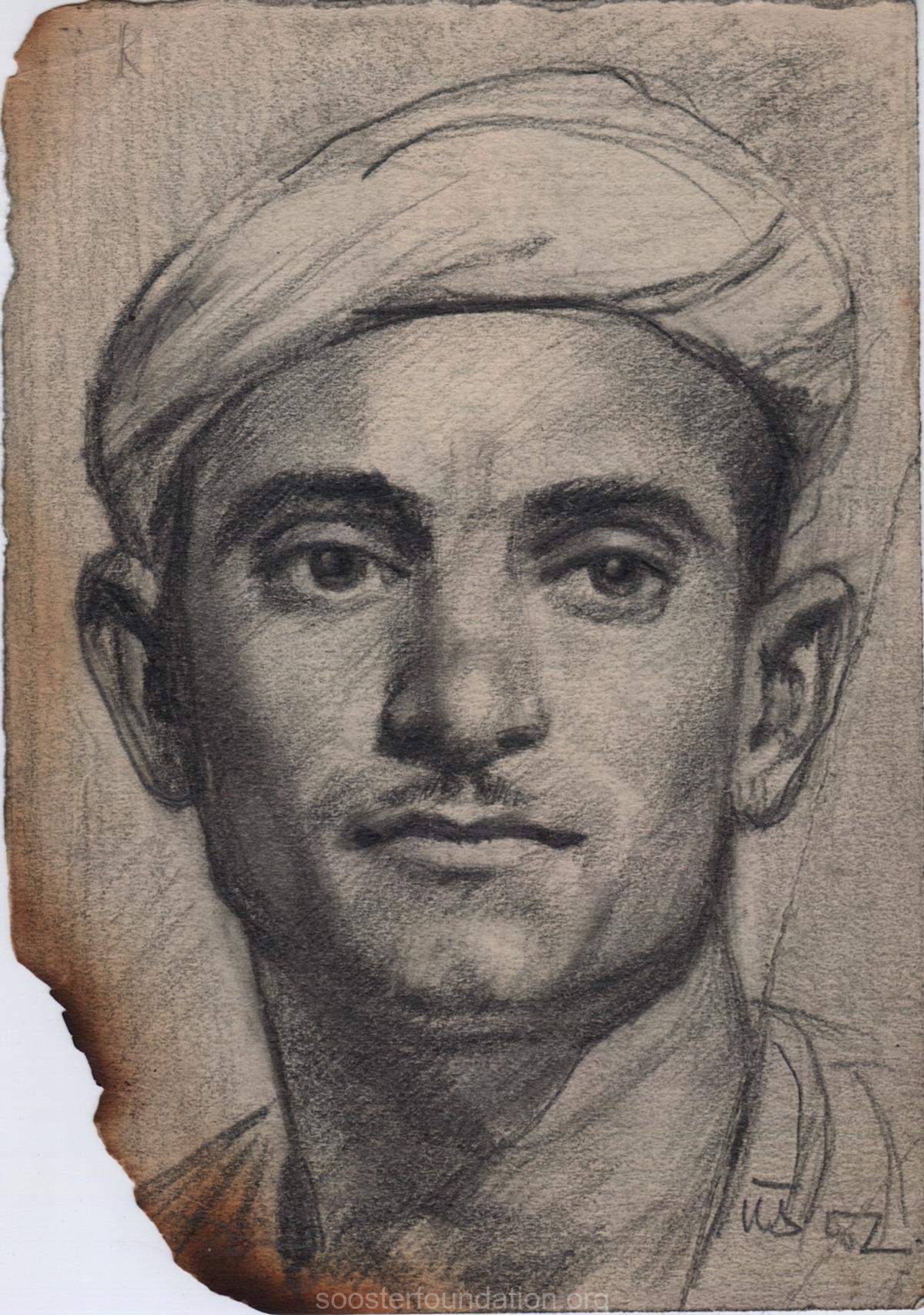

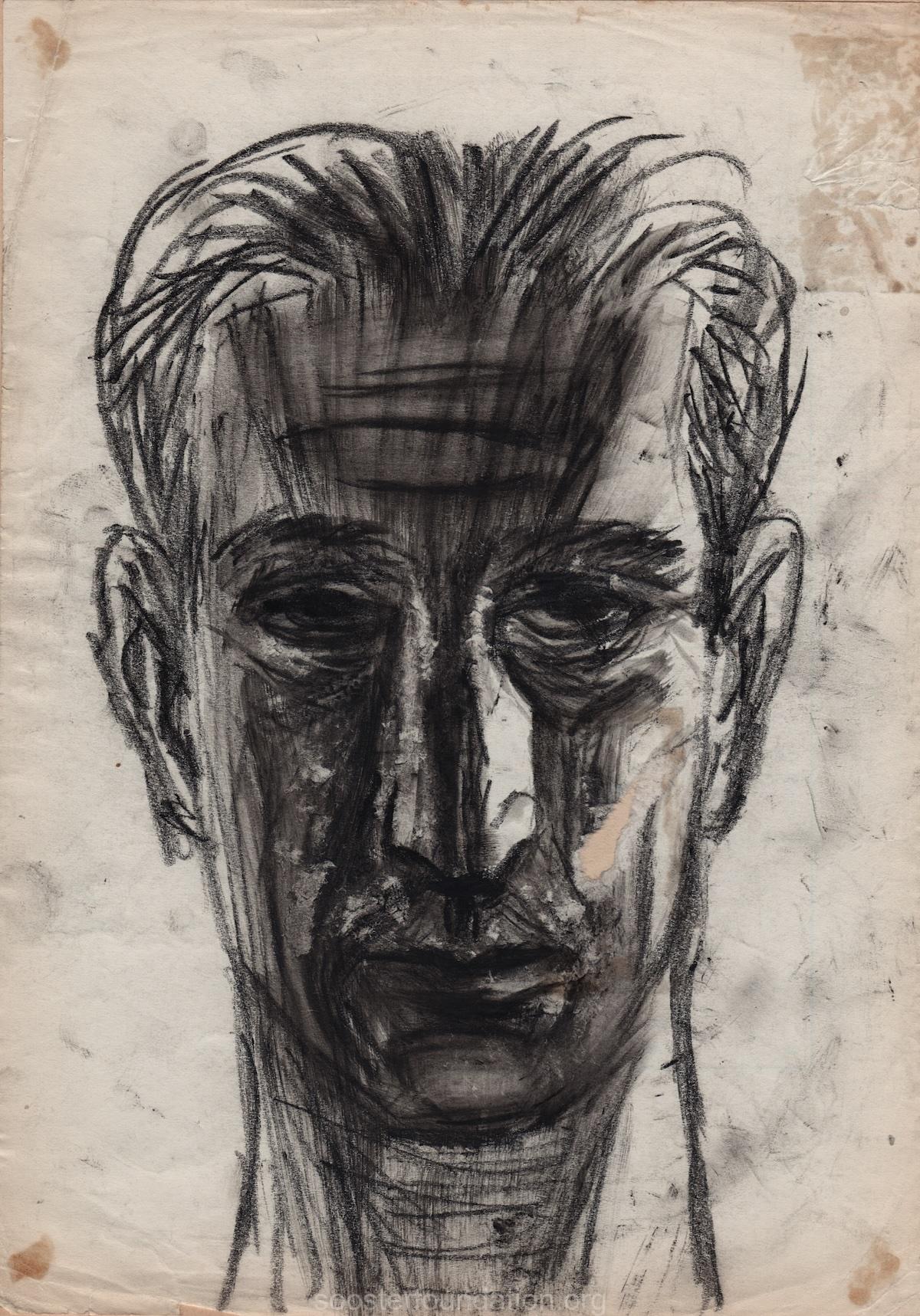

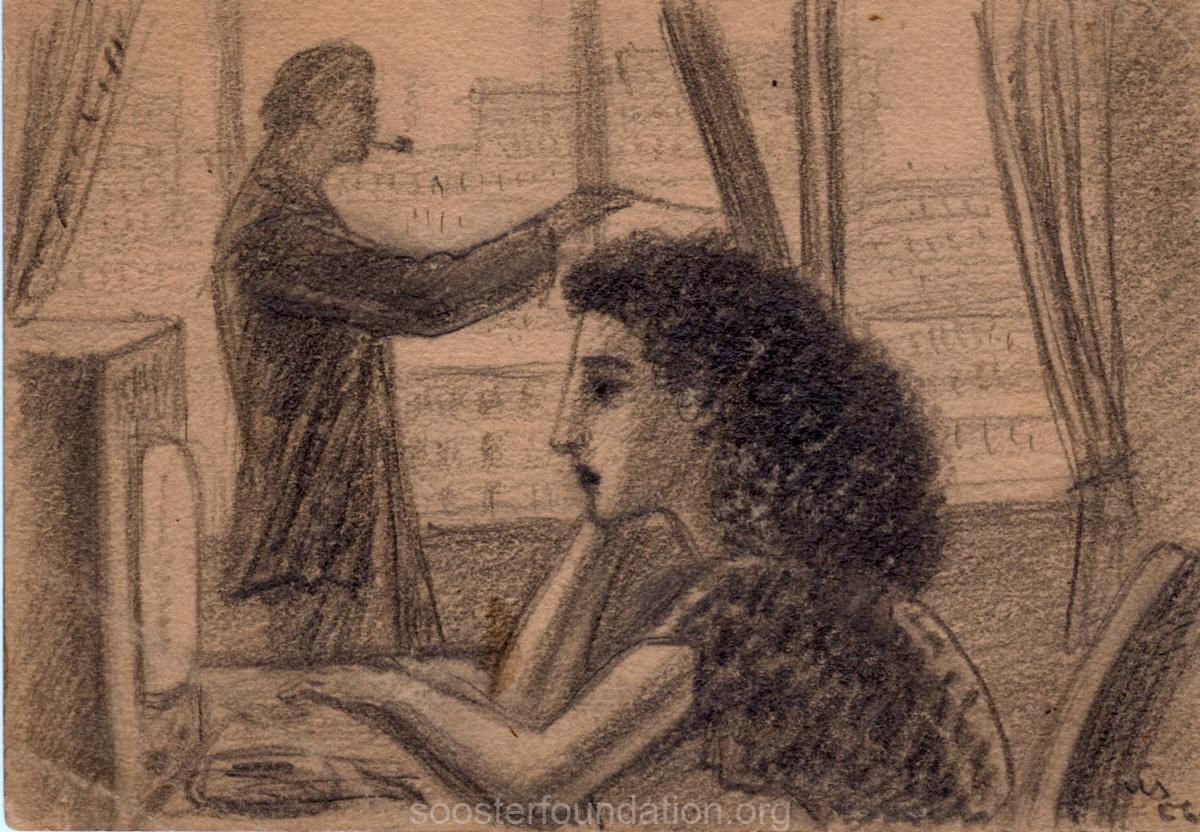

Among the portraits of prisoners, there are a few where one can recognize Andrei Solovey, who would later become a well-known photographer, art theorist, and teacher. In the camp, Sooster and Solovey bonded over their shared interest in art.

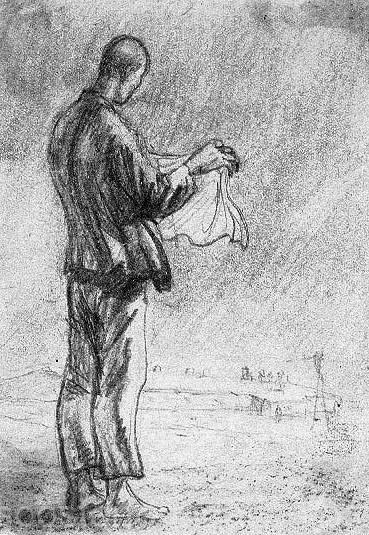

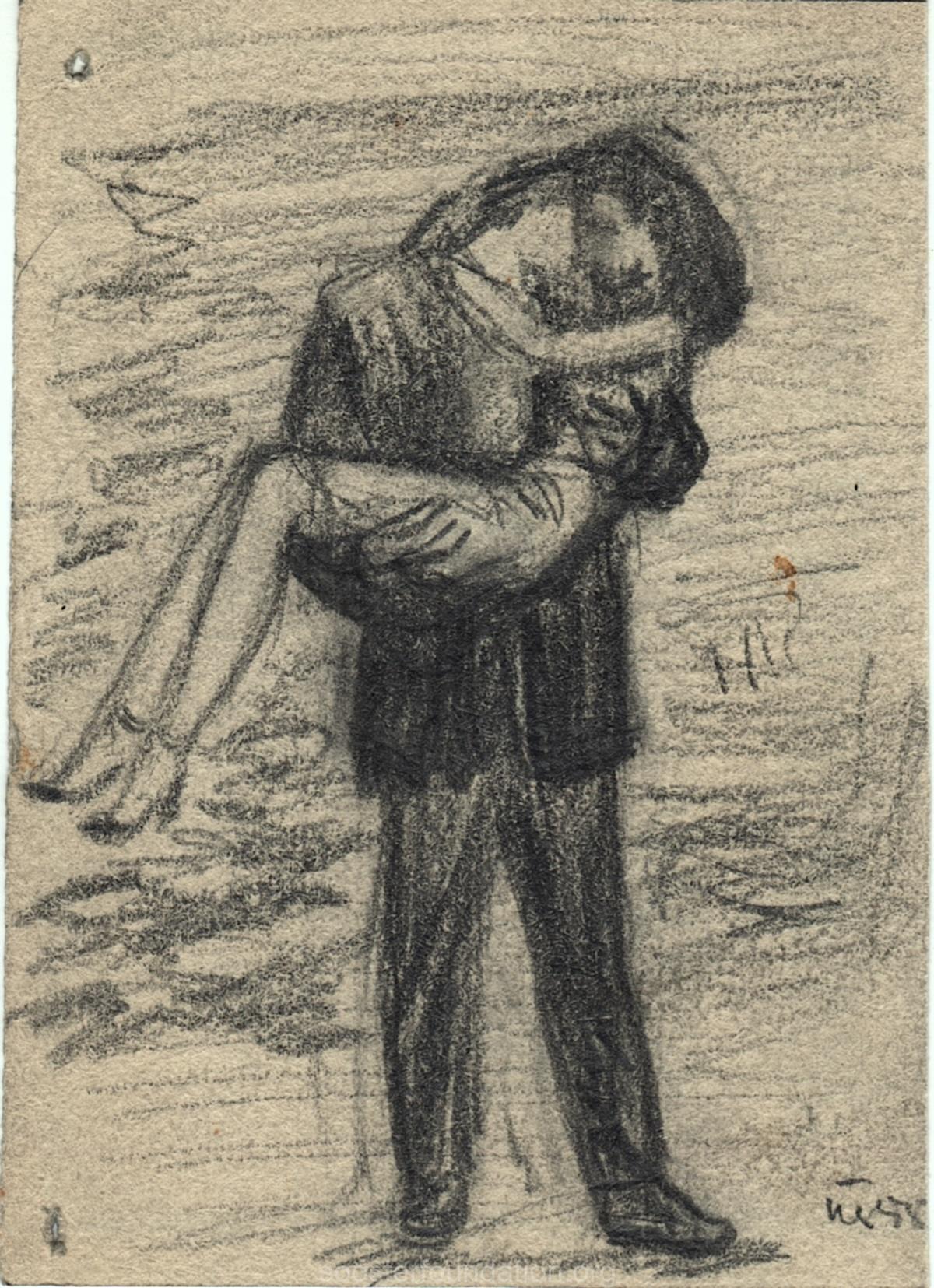

"Ülo loved drawing Andrei very much; he portrayed him dozens of times and, after a while, would return to the portraits again," recalled the artist’s future wife, Lidia Serkh. One of the most famous genre drawings depicts a prisoner from the back, holding a handkerchief that flutters in the wind.

"A man stands – a prisoner – holding a handkerchief stretched between his fingers. He’s drying it. He washed it and now is drying it. But where can he hang it? It would be stolen! In the drawing, the man’s face and his strange pose are so significant, so serious... No, this is not just an everyday scene or a sketch of camp life. The man is holding his pure soul in his hands and won’t let it get dirty. And the Gulag, the bunks, the thieves, the guards – all of that is lower, all of that is beyond," wrote Ülo’s contemporary, artist Anatoly Brusilovsky, about these works.

Portraits made up a large part of Ülo Sooster's camp drawings. On one hand, Ülo drew prisoners to earn a living – the portraits replaced photographs for the prisoners. They would commission the drawing and, if possible, send it home along with a letter. On the other hand, by drawing prisoners, Ülo was honing his drawing skills – "the foundation of everything," as his teachers at "Pallas" would say. With pencil, ink, and charcoal – just as he had drawn models in the institute's classrooms and friends in the cafes of Tartu.

Nikolai Maslennikov, known as Kola-mustache, was also a prisoner and an artist. Ülo drew him in the camp. Their friendship continued for years, despite the distances. Until Ülo's death in 1970. At that time, both Andrei Solovey and Nikolai Maslennikov came to Moscow.

1956

The 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union took place, where Khrushchev delivered a report denouncing the cult of personality surrounding Stalin.

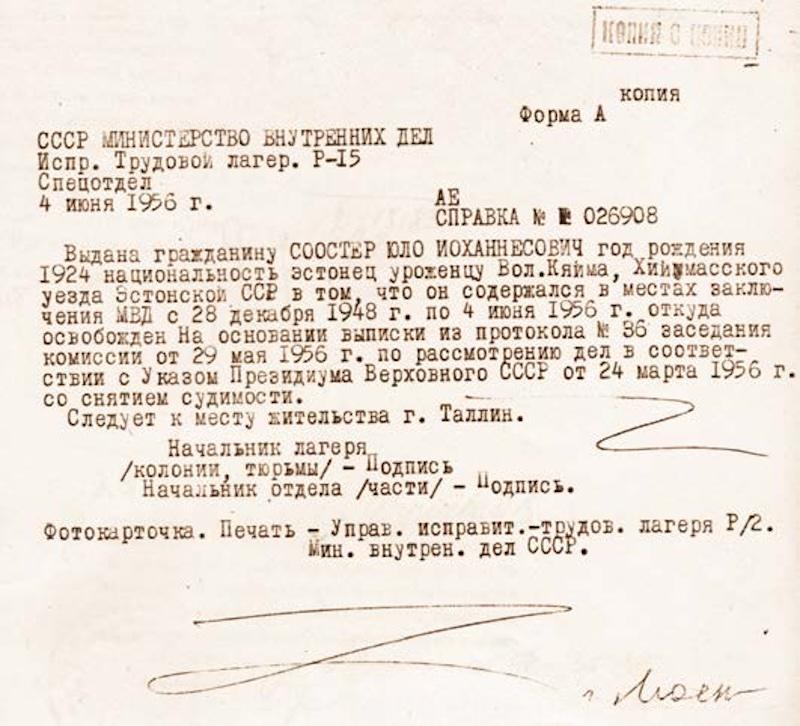

Prisoners submitted petitions for the review of their cases. Commissions were established to release political prisoners on site.

KARLAG. A LOVE STORY

"Before us is one of the greatest love stories in this world, written in the first person. But Paolo and Francesca, Perseus and Andromeda, Orpheus and Eurydice, Dante and Beatrice, Cephalus and Procris, Tristan and Isolde somehow succumbed to the ruthless world, while Ülo and Lidia overcame it. A plot fit for Hollywood..."

Andrei Kovalev, critic, on Lidia Sooster’s book My Sooster, Tallinn, Avenarius, 2000

1954

In the autumn, at the exhibition of the labor camp achievements in the House of Education in the settlement of Dolinka (Karlag), Ülo Sooster met his future wife, the artist Lidia Serh, who was a prisoner in the neighboring camp.

Years later, she would write: "Could I, an ordinary Jewish girl from Moscow, have predicted that I would go through camps, deprivation, nightmares, and sorrow, and meet and fall in love with a person I would not have met under other circumstances? However, as with everything in this crazy age, what happened happened."

Lidia was born on September 23, 1926. A regular and music school, books, theaters, friends, and a beloved city. When Lidia was 15 years old, the war began, and in 1943, she was arrested and sent to three years of exile in the Krasnoyarsk region "for espionage and connections with American intelligence." In plain language, this meant she was arrested for communicating with American pilots who were delivering equipment to Moscow under Lend-Lease. Only a strong and resilient person could endure humiliation, hunger, cold, and hard labor – endure it and not lose themselves. In 1946, Lidia returned to Moscow and enrolled in an art school in the toy department. In 1950, she was arrested for the second time for "espionage and anti-Soviet propaganda" and sentenced to seven years in a labor camp.

In the autumn of 1954, Lidia Serh was tasked with organizing an exhibition of agricultural achievements for her camp point. The prisoner Ülo Sooster was responsible for organizing the large exhibition. This meeting, without exaggeration, became fateful for them.

On October 17, Ülo turned 30. Having access to paints, he painted his self-portrait – a face distorted by a scream. The work would later be called "Fear."

1955

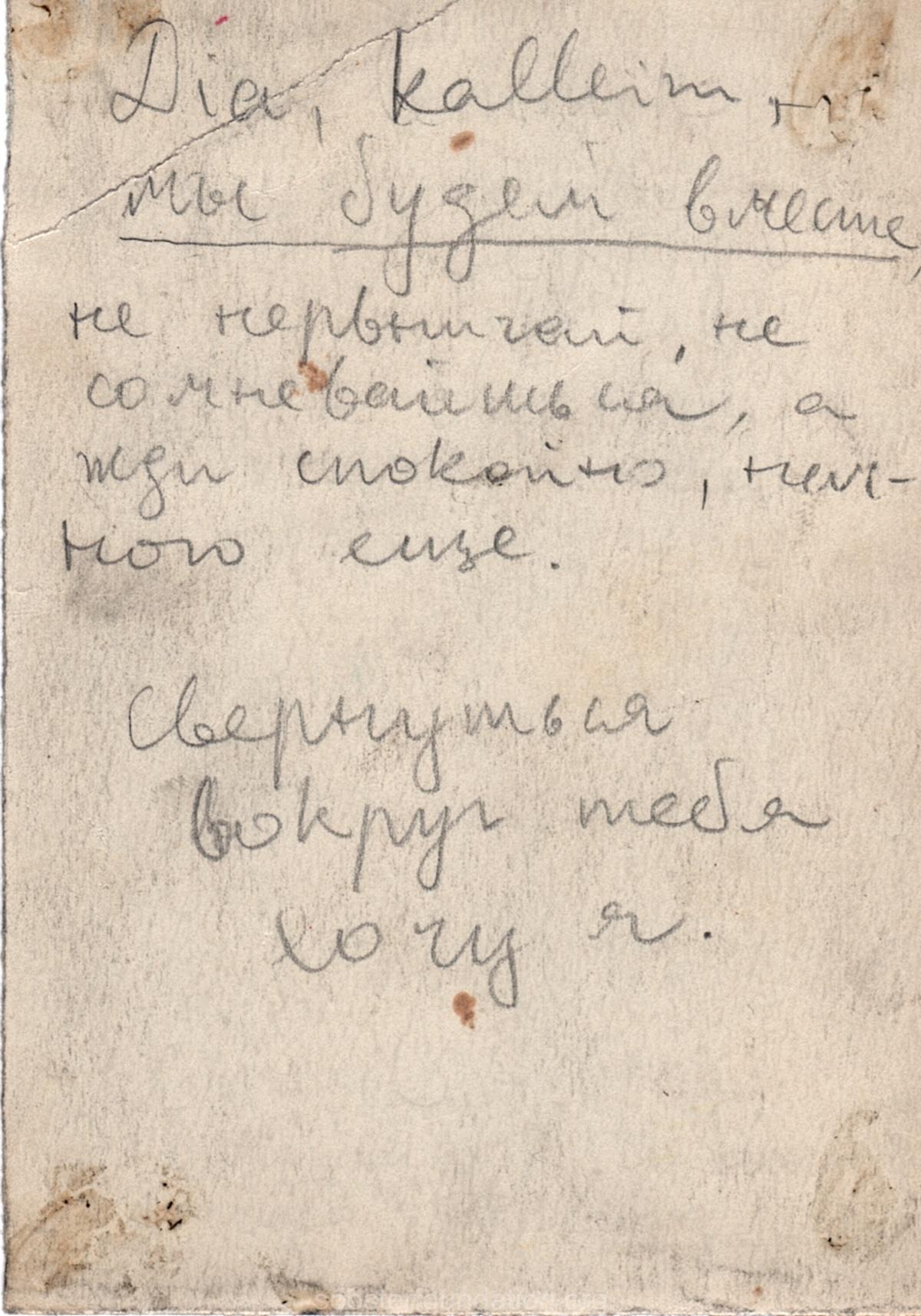

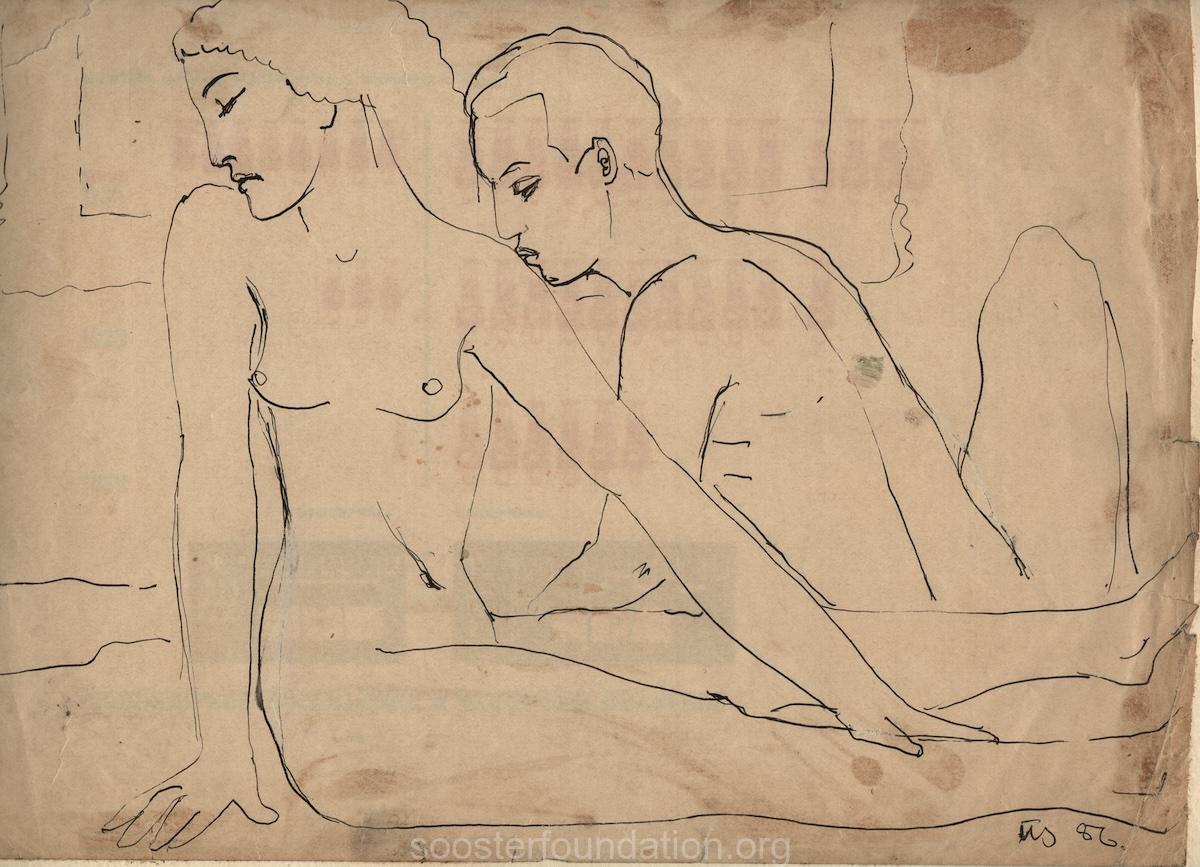

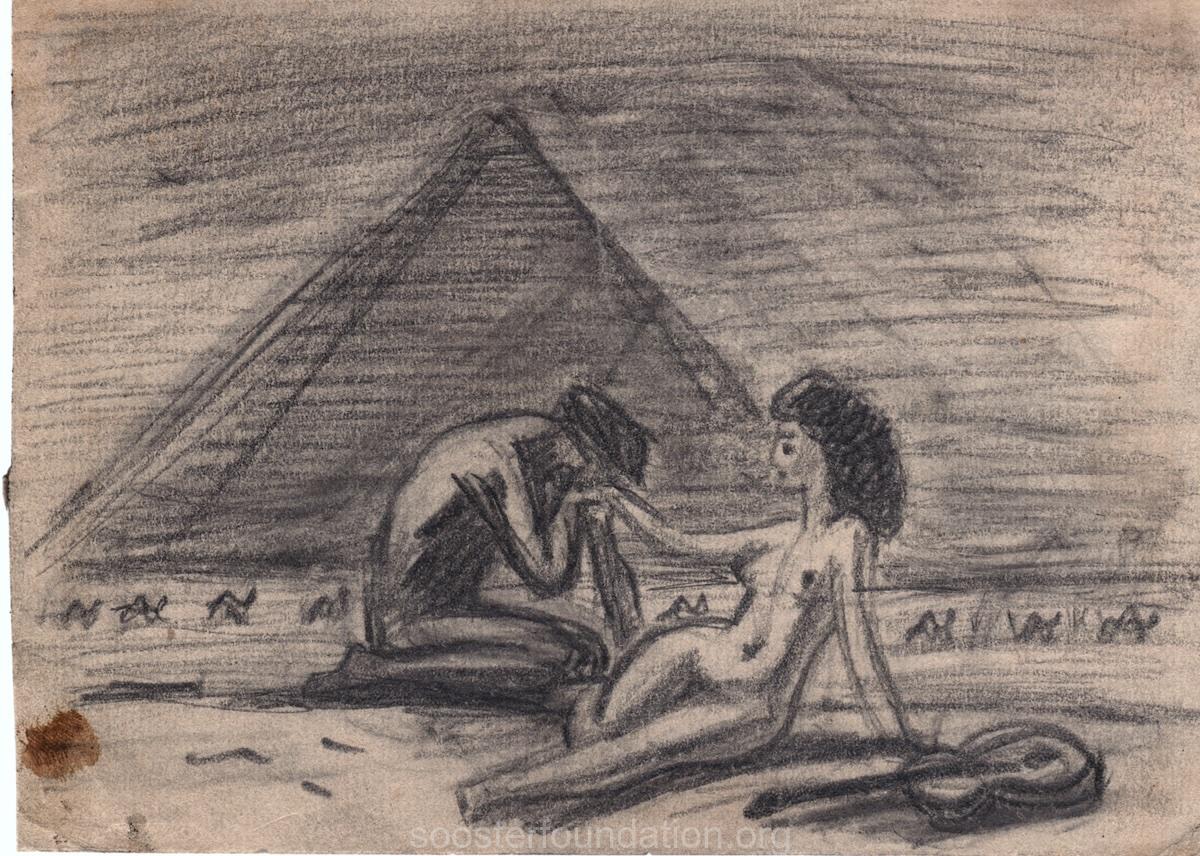

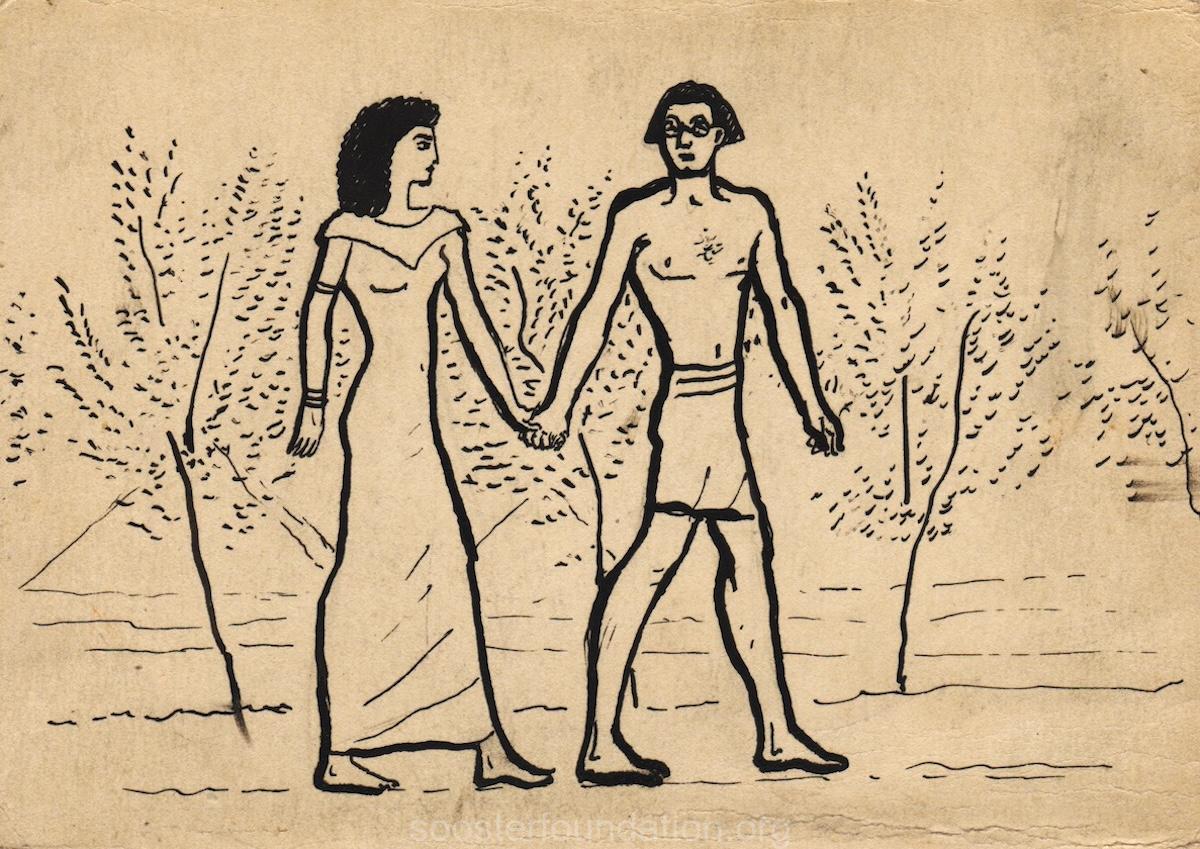

He draws a lot and sends not only letters to his beloved but also fantasy drawings, drawings of intimacy, and drawings of a happy family life.

Sometimes he manages to paint in oil, including self-portraits.

In December, Lidia was released. Without permission to live in the capital, she was forced to live in the Vladimir region. "The only joy was the letters from Ülo, in which he asked her to wait and hope."

1956

On April 30, Lydia returns to Karaganda. Ülo manages to obtain permission to live outside the camp and rents a room. He begins to secretly carry out the canvases and graphic drawings he has accumulated over the years from the camp. Those that were rescued from the fire have burned edges. They were saved because they were tied in tight bundles.

On June 4, Ülo Sooster was granted amnesty and received permission to return to Estonia.